OLE UKENA : WEARING YOUR ART ON YOUR SLEEVE

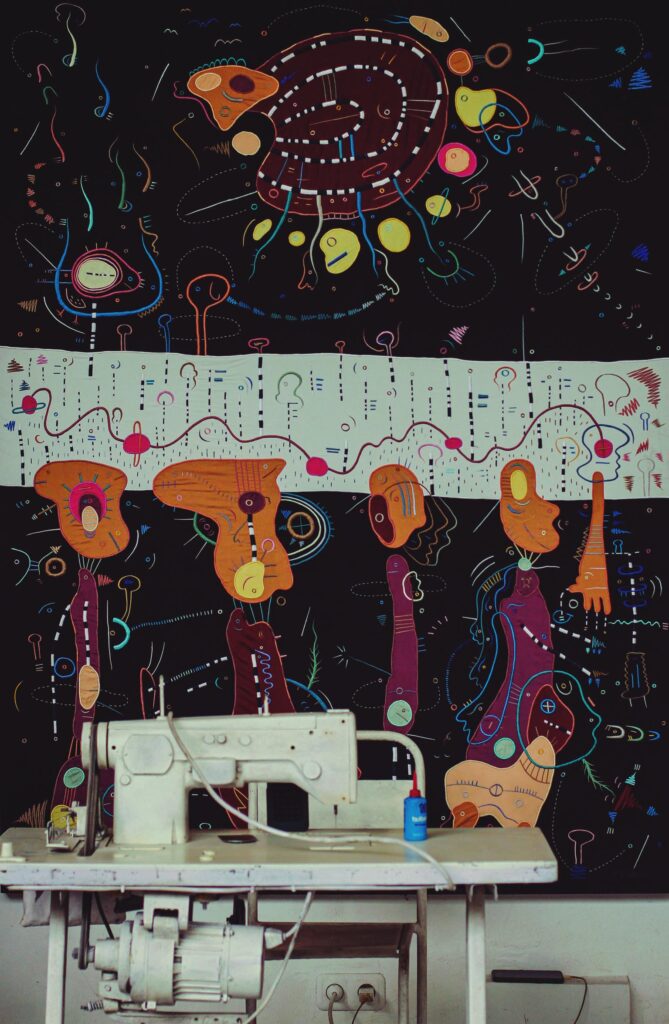

Ole Ukena is a self-defined “multidisciplinary artist from Berlin, who interweaves traditional textile and embroidery, creating works located in the in-between space of abstraction and figuration”. His studio is located in Ubud jungle and CUB recently met with him to discuss the space where art meets fashion, the complexity of technicality and the beauty of collaboration.

Pandemic changes and that sweet spot where art and fashion combine

The pandemic has had some strange auspicious effects, when change happens often something new and exciting comes of it. This was certainly the case for Ole Ukena, the successful artist ended up stuck in Ubud during the travel ban with no exhibition on schedule, and, so, he decided to do something radically different.

Aware of the adverse effects of fast fashion and wanting some good quality innovative apparel, he decided to make clothes for himself. Already connected to local cloth makers and embroiders, he soon had put together a team and decided to get involved in the whole process from scratch: from making the cloth, to tailoring, to printing, to embroidering, now that there is interest, to selling. The idea was to know the people making the clothing throughout the chain from weaving the material until the item is sold, in the respect of ethics and the environment.

At first, it was fully the art influencing the clothing, the clothes range reflected items from the Berliner’s art, and were just a new canvas; but with time the opposite also started to happen; creating the clothes had an impact on Ole’s art: “sometime, now, I’m working on an idea for clothing and suddenly it gives me new ideas for my art and can influence my next piece. The lines are becoming more blurry. Before it was only in one direction but now it’s like a counter counter-process (laughs)”.

Bringing more democracy to buying art

After completing his first set of clothing and posting some pictures on social media saying simply “oh look, I made myself a jacket”, Ole garnered a lot of interest. A dozen people immediately asked if they could purchase a piece of clothing for themselves. What had started out as a solo adventure to make clothes for himself, suddenly turned into a way to make his art more accessible to smaller wallets, it was like “10 times 500 euros”, a completely different price range. Ole remembers that “for me, it was more democratic all of a sudden, not just in a gallery” and it changed his outlook. All of a sudden new doors opened: “why not get involved in other forms of artistic expression, through decoration or furniture as well ?”.

Unexpected challenges of embroidery

However, making clothing is a complex endeavour, especially from scratch and especially when you include digitally scanned artwork which you then embroider. The first challenge was creating the cloth. Ole wanted to make most of it through his own channels and is now making approximately sixty to seventy percent of the total used. He uses organic dyes which are great environmentally but, problematically, they tend to fade rapidly.

Another issue he encountered was how to make his scanned designs fit on different sizes of clothes. He creates digital prints from manual work which has made it much more possible to adjust for sizes even though the technique remains very complex. He scans his drawings and paintings destined to the fashion range then digitalises everything so that he can adjust the size of the design by a few centimetres to fit the different clothing sizes. He explains ; “To jump from size S to size L, you have to digitalise everything, then make the design three centimeters bigger, print it out, do manual roll holes, to then draw it with the chalk, is a very crazy process. People don’t understand the complexity of the process of working with embroidery.” What he finds interesting in the scanning process, though, is that the feeling of the texture remains, and once printed, it’s embroidered on top, so, as he says “your brain is a little bit confused” in understanding the exact process of creating the patterns, prints and embroidery on his clothing range.

The beauty of collaboration

Ole mentions the importance of collaboration in art and how it happens in many different ways. There is a collaboration between the artist and the people who see the art and who bring their own understanding and sensitivity to what they see. The artists may give a piece a cryptic title so someone else can imagine a wholly different interpretation to the artwork, and sometimes that comes back to, and, in return, influences the artist like a virtuous circle. ”I really like the poetry of the viewer completing it, and on certain days, you discover new elements of it. So it’s this line that I am interested in “.

He likes “building the entire structure in a way that I’m challenged to meet other impulses, then my own again.” Being cross-disciplinary, he welcomes collaborations with other artists from different backgrounds, for instance, a photographer from Russia. He thrives on “figuring out ways in which two different worlds can create something that’s a combination of both. The decision-making stages in those merging processes are very interesting” to him. He mentions the beauty of mixing one’s own capabilities and mindset with someone else’s and then creating something that is both and neither.

Sometimes collaboration is needed just to complete a project that the artist has in their head. For instance, the artist might want to explore the “metaphorical potential of nails” by making an art piece with 50 000 nails; but, putting them all on a board alone might take a month and they may not go ahead with it or might “become a contractor of their own ideas“. So, if they have money and a studio with 20 people they can complete it through this collaboration. For instance, Ole makes all the shapes and designs on the clothes but these are then embroidered by the women who specialise in this craft, so he relinquishes part of the creative process to them.

This is reflected in his relationship to handicrafts. Being in Bali, he is surrounded by traditional craft techniques, and what he finds exciting is “putting them in a contemporary context”, which may not come to mind to the people making these handicrafts without an external impulse. The stimulating side is combining traditional elements with the discourse that is happening artistically at the moment. He sees it happening with other artists too with other media and materials.

Bali creative playground

The artist concludes that despite Bali bringing inspiration and opportunities to him thanks to the handicrafts and collaborations present and surrounding him, ultimately, the source of his creations comes from the inside . “It’s a very internal process: I would create the same way no matter what the surroundings are, I draw on the subconscious so I don’t draw from looking outwards but from looking inside”.

Even so, Bali has allowed him to develop a fascinating new hybrid of art and fashion by mixing his modern artist sensitivity with age-old balinese handicrafts and embroidering techniques.